2023 Faith & John Gaw Meem Preservation Trades Internship Report by Giulia Caporuscio

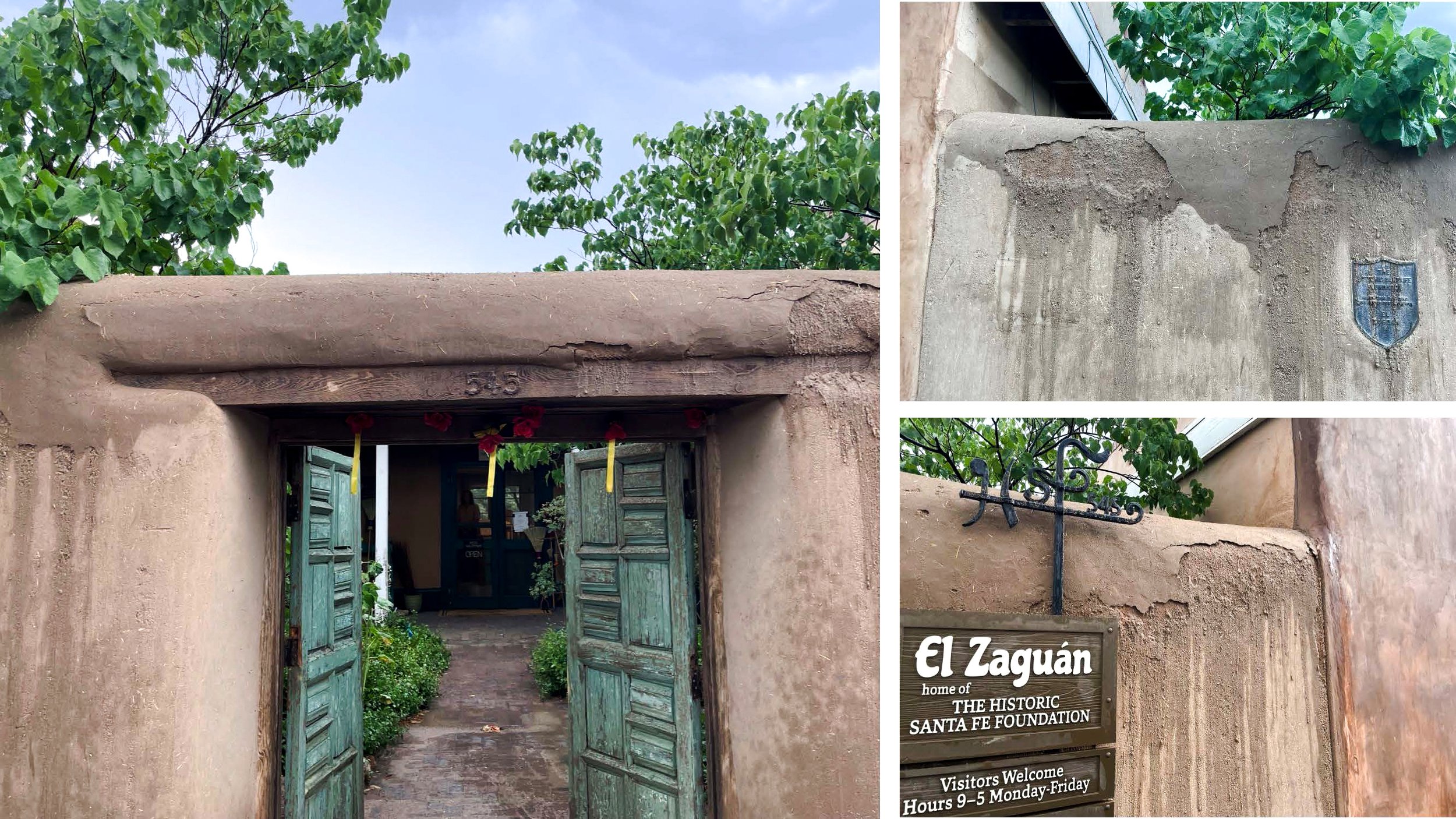

/Front Wall Saga

The summer started with a week of getting to know the lay of the land at El Zaguán as the Historic Santa Fe Foundation’s (HSFF) 2023 Faith and John Gaw Meem Preservation Trades Intern. Any spare time I had I spent familiarizing myself with the Foundation’s preservation easements. The second week HSFF Preservation Projects and Programs Manager Jacob Sisneros and I went straight to work plastering El Zaguán’s front wall. Don Sena, from Cornerstones Community Partnerships, collaborated with us, supplying the materials, and teaching us the tricks of working with adobe. The mixture was equal parts sand and clay, with a slightly gray hue. The wall was not in terrible condition but had a few holes in places. The previous mixture had been too sandy, and a colony of ants took up residence in the top. With Don, Jacob, and I working on the wall we finished in three days, with half a day spent mixing and hauling more sand and clay. A bonus was going with Don to San Miguel Chapel where he gave me a full tour of the work and renovations there and pointed out some archeological finds. This visit included laying electrical cables in adobe walls, hard troweling, applying lime plaster, and dry packing around windows and doors.

The rain on June 25, took down the cap of the wall. On July 26, we replastered the cap with the leftover mix we had from the second week. This time we tried adding Elmer's glue to the mix, to see if the polymer would help against monsoons. This trick is used at Las Golondrinas for all the final plaster. The addition of Elmer's glue changed the consistency of the mud mix, creating a non-Newtonian liquid, making it easier to trowel onto the wall but harder to hold and place the mud. It also made the mixture drier. I noticed that the wall needed to be soaked before the mixture was applied, then I would throw the mud on, wet that, then trowel it smooth. Then for good measure wet the new patch before troweling again. The final cap came out smooth and more scratch proof than with the previous mix. It did not hold up against the rain of August 8th. Parts of the new cap remained, but the wall was still wet two days after the big rain. The moisture in the wall meant that more of the plaster peeled off during the next day. In one spot the adobes were exposed, the same spot that had a huge hole at the beginning of the summer. (It appears that the tree next to the wall directs water into that spot). It is discouraging the damage done to the wall, but it is a reminder that this is just mud, it is a material that came from the earth and will return to it, it is still in sync with the climate and reacts to the weather. It is a material that does what is needed but requires more maintenance, however, does not exploit or harm the environment when it fails. The process of remudding the wall is in tune with the cultural practice of New Mexico and mirrors the reality of generations of people in the greater Southwest.

Las Golondrinas Adventures

My main project at Las Golondrinas was the rebuilding of an horno. The original horno was over twenty years old and the adobe walls had become too thin to hold heat and properly roast the green chilis it was most often used for. The first job was to demolish and haul away the dirt from the old horno. After this I discovered that the floor of the horno was originally a cement circle, with a packed earth floor beneath. The next process was clearing out and leveling the ground to lay bricks to create an even, easy to clean floor for the horno. Then came the process of laying the adobes. The adobes were trapezoidal blocks specially ordered from Adobe Man in Santa Fe.

I played around with the layout of the adobes to determine the best size and structural pattern. Since the layout was circular, I soon realized that I needed to fill the mortar in between neighboring adobes with adobe shards so that there were not huge gaps of mortar that would change shape as the horno dried. This process was slow. Every level had to dry completely before building the next round to prevent settling. That and the summer temperatures required a water break every fifteen minutes. When I was four courses in, I plastered the interior before I would no longer be able to fit my arm inside. Then I finished the arch with a keystone. I added a port at the back and closed off the horno in two more courses. The rest of my time on the horno was spent evening things out and creating a dome on top, rather than a flat top. I plastered the exterior with the Elmer’s glue mixture, then we lit the inaugural fire inside.

The rest of my time at Las Golondrinas consisted of plastering and wall repairs. These projects included a pair of buttresses, the wall along the ram enclosure, the comal, and a small wall next to the sheep enclosure. There was some relief in this work since most was shaded. Really hot days required the workday to start at five in the morning to avoid the sun. The heat could also be seen in the plastering. Many places had some minor cracks in the plaster since the new work would dry too quickly. Las Golondrinas was a quiet place to work and plaster, especially when I would get there hours before the visitors or other workers. I made friends with a goat in the ram enclosure, saw hawks, ospreys, vultures, hummingbirds, hundreds of lizards, toads, frogs, and scorpions. I answered many questions from tourists, most often about what was in the mixture.

Student Workshop

One of my favorite events from the summer was the student workshop with the Santa Fe Children’s Museum Youth Conservation Corps. Five high school students participated in the workshop. I enjoyed showing them how to mix mud for the adobes and lay them into the forms, while trying to answer their questions on how to identify a true adobe building around Santa Fe.

Wood Working

An unexpected skill from this summer was learning some basic woodworking skills from Jacob. I had used some power tools before, but I gained more confidence with them, learned more safety precautions for them, and ultimately how to respect the tools. The first project was building a frame for the arches built at the youth workshop. This included working with an electric jigsaw and cordless drills. Our biggest project was building a crate to protect an artifact. This taught me how to use a circular saw to cut all the wood pieces to size. The last project I briefly worked on was refurbishing a table. This taught me about belt sanders and orbital sanders.

Preservation Knowledge

The skills I can add to my resume following my internship at HSFF include conditions assessment, site maintenance, fundraising and party planning, preservation easements, and familiarity with nonprofits. As I said going into this, I wanted more practical experience in historic preservation, and I am so grateful for what I have gained this summer. I saw my skills in plastering, creating mud mixes, and estimating how much material is needed increase greatly. I have seen so many beautiful examples of historic preservation from the J.B. Jackson House to Los Pinos Guest Ranch, Oppenheimer’s house, and behind the scenes at El Zaguan, Las Golondrinas, San Miguel Chapel, and a few easement properties.

I am most grateful for the people I have met this summer and the insights I have received from them. Pete, Melanie, Hanna, and Jacob at HSFF, Sean and Cesar from Las Golondrinas, and Don Sena from Conerstones Community Partnerships. As well as the HSFF Board of Directors and Property Committee Members.